Historical Documents

A treacherous web of laws, financial systems, and political posturing sustained the British transatlantic slave trade. These documents that range from charters and court documents to a drawing of a slave ship and an advertisement for a slave ship's arrival illustrate how deeply slavery was embedded in Britain’s political, legal, imperial and economic structure.

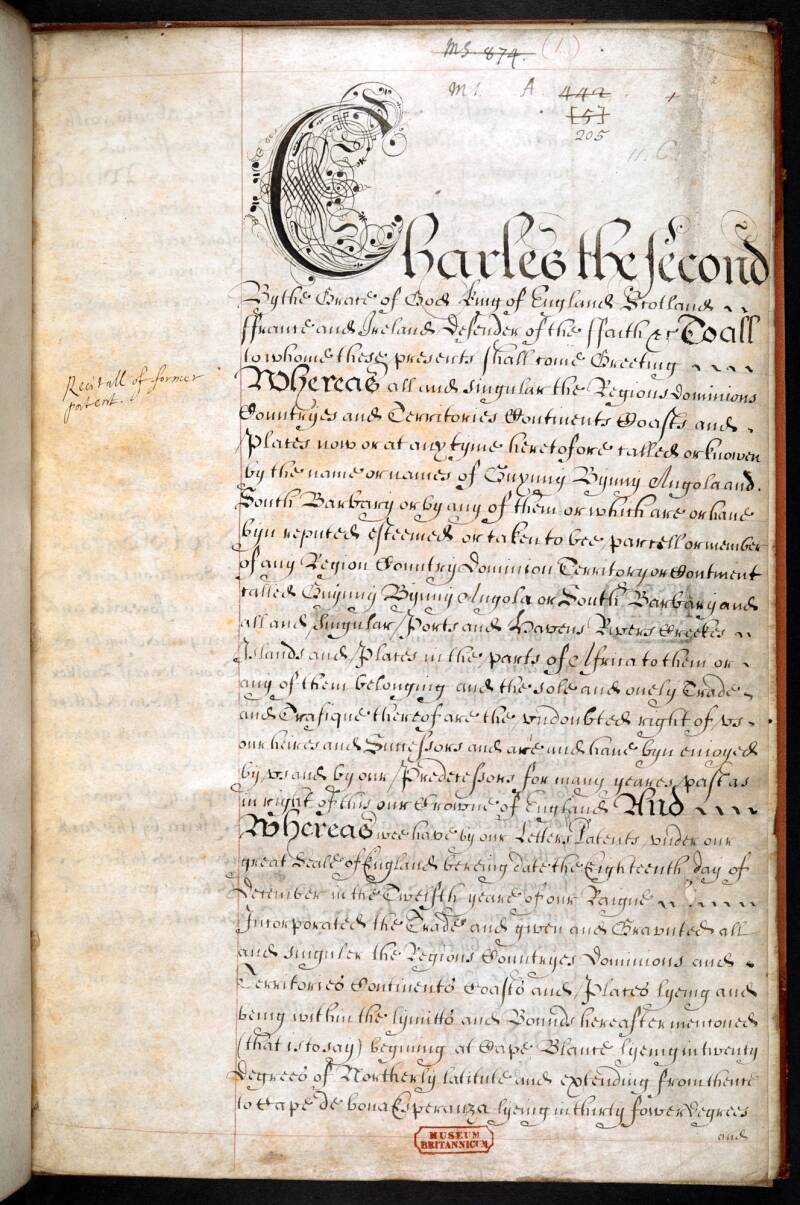

Royal African Company Charter (1663)

Granted by King Charles II, this charter authorized exclusive rights to the Royal African Company to trade in West Africa, including the trade of gold and enslaved Africans. This charter institutionalized Britain’s participation in the slave trade and tied it directly to the Crown and powerful investors who grew their wealth enormously (Charles II).

The Transatlantic Slave Trade Video: Slaves as Commodities

Historian S.I. Martin examines a couple of documents from the British Slave Trade.

The first log lists names that were given the slaves by their owners. This slave log shows that the Africans were stripped of their cultural names and given English names, further distancing them from their cultural roots.

Another document lists individual slave descriptions and crafts alongside their monetary value, proving that slave owners and traders viewed slaves as a financial commodities, not as humans with dignity (“Documents Relating a Case in the Court of Kings Bench Involving the Ship ZONG).

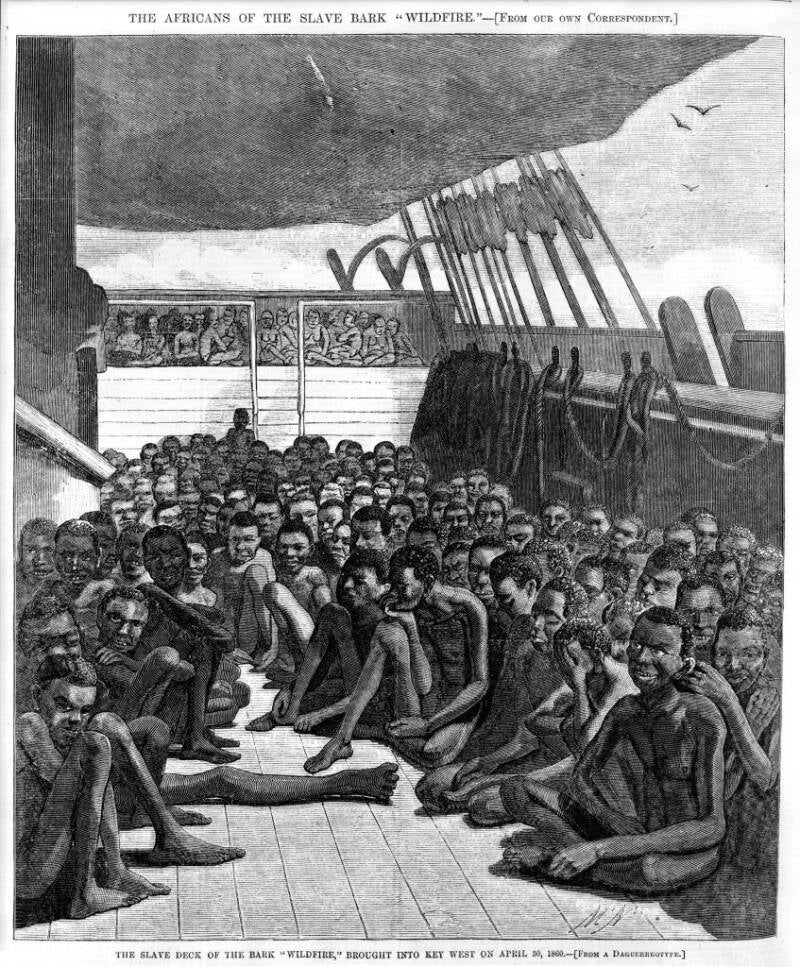

“Description of a Slave Ship” (1789)

On the left is a document originally printed by James Phillips for the London Committee of the Society for Effecting the Abolition of the Slave Trade. This famous diagram shows the horrific overcrowding on slave ships. It became one of the most influential visual tools of the abolition movement, widely circulated across Britain (Phillips).

The picture on the right is an example of the crowded conditions that Africans endured on the ship across the ocean (Wolfe).

Account Book from Slave Ship Molly

These pages from the slave ship' Molly's 1758-59 account book show that traders considered the sale of slaves to be business as usual without regard for their human qualities. The Molly left Bristol, England, traveled to the African shoreline and the Caribbean, before finally returning back to Bristol, completing the triangular trade route.

Sadly, this ledger proves that the Africans were considered commodities. They were treated like cargo and denied even the most basic rights. A description of the slave (man, woman, boy, or girl) is found in the first four columns and the other columns show the goods that were traded for them. For example, on row two, one African woman was brought forward from Jack Pepper in exchange for all the goods that are marked on that row (Understanding Slavery Initiative).

The Zong Massacre Legal Case (Gregson v. Gilbert, 1783)

Court records reveal the tragic massacre of over 130 enslaved Africans who were thrown overboard and treated as an insurance dispute rather than murder victims. The case epitomized the dehumanization of enslaved people under British law and helped galvanize abolitionist activism, serving as a turning point in the fight to end slavery (Baksi).

At the right is a court document from the legal case documenting the tragic Zong Massacre (“Documents Relating a Case in the Court of Kings Bench Involving the Ship ZONG").

Advertisement for a Slave Sale

Over 2.75 million enslaved Africans arrived in the Caribbean British islands between 1600 and the end of the Transatlantic Slave Trade in 1808. The numbers of enslaved people greatly outnumbered the whites and free people in the colonies. In fact, in 1788 Jamaica, about 90% of the island's population were slaves – out of the 250,000 person population, 225,000 of them were slaves. They arrived by ships after a dangerous journey across the Atlantic Ocean. Newspaper advertisements announced the arrival of the ships at the many busy ports and the subsequent sale of people who deserved better. When the Africans finally made landfall, they were held in captivity by merchants until they were sold (Caribbean Port Towns – the Saint Lauretia Project).

This flyer is found in the Antigua Journal (St. John’s), Tuesday 26 February 1799, pg.1. Courtesy of the American Antiquarian Society (Caribbean Port Towns – the Saint Lauretia Project).